In cross-border e-commerce, social media operations, advertising, and other scenarios, more and more users are coming across a concept: Fingerprint Browser.

Most people are not interested in the browser technology itself but encounter issues during actual use, such as account association, frequent verification, limited functionality, or even being banned without obvious violations. What’s more confusing is that these problems often recur, and even changing IPs, clearing cookies, or logging in again does not completely resolve them.

These phenomena actually reflect a change that is happening:

Platforms are shifting their judgment of users from "single parameters" to "overall usage environment".

Why are platforms starting to care about the "usage environment" rather than just the IP?

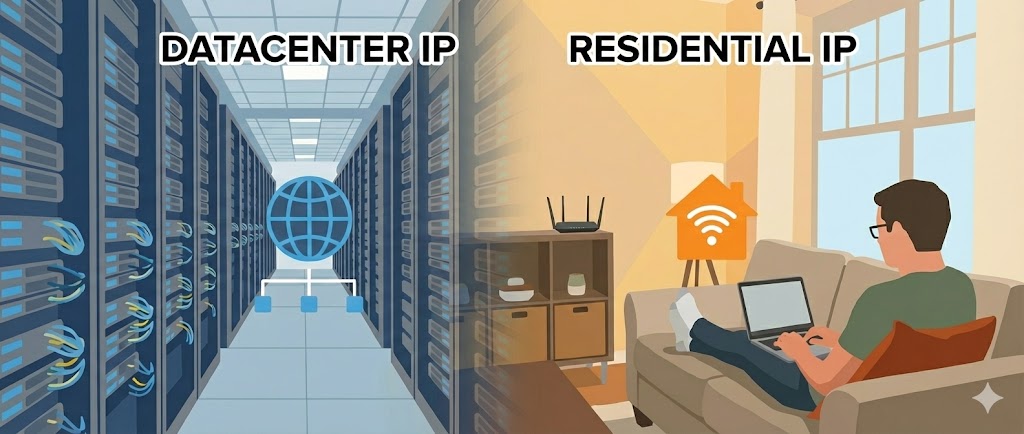

In the early internet environment, the IP address was one of the important bases for distinguishing users.

However, with the popularity of proxy services, VPNs, and other tools, it has become difficult to determine whether access behavior comes from the same person based solely on the IP.

As a result, more and more platforms are adopting more complex judgment logic.

They are no longer just concerned about "where you come from" but are trying to answer a more fundamental question:

Do you behave like a real user who has been consistently present over a long period?

To answer this question, platforms typically analyze multiple signals, such as:

- Whether the device and browser environment you use are consistent over a long period

- Whether multiple accounts share obvious device characteristics

- Whether operational behaviors exhibit high repetition or abnormal switching

In this context, merely changing the IP is often insufficient to resolve account association or risk control issues.

What is a Fingerprint Browser?

A Fingerprint Browser is essentially a "browser environment management tool".

Its core function is not to hide identity or bypass rules, but to create multiple independent and isolated browser environments on the same device. Each account operates in its own independent environment, thereby avoiding being identified as the same user by the platform due to shared device characteristics.

To put it in a more understandable way:

Regular browsers are like switching accounts repeatedly on one computer;

A Fingerprint Browser simulates multiple different computers on one device.

This "simulation" is not simply about opening multiple windows but involves more fundamental browser environment parameters.

What is a Browser Fingerprint? How do platforms identify you?

A Browser Fingerprint is not a single information point but a combination of device and environmental characteristics that can remain stable over a long period.

Common browser fingerprint information includes but is not limited to:

- Browser type and version (User-Agent)

- Operating system information

- Screen resolution and display parameters

- Time zone, language settings

- Font list, plugin information

- WebGL, Canvas, and other graphic rendering features

These pieces of information do not have strong identification capabilities when viewed individually, but when combined, they form a highly stable "device profile".

This is why, even if users clear cookies or use incognito mode, platforms still have the ability to determine whether multiple accesses come from the same device.

From the platform's perspective, it is not concerned with "what operations you performed" but rather:

Whether these operations consistently occur within a reasonable and stable usage environment.

How does a Fingerprint Browser work?

A Fingerprint Browser typically achieves environmental isolation through browser profiles.

In practice, it creates an independent browser environment for each account, with each environment having its own local data and fingerprint parameters, such as:

- Cookies and local storage are not shared

- Fingerprint parameters (such as resolution, system information, etc.) are distinguished from each other

- Login status and browsing history are completely isolated

As a result, from the platform's perspective, the access behavior of each account appears to come from an independently existing "device environment" rather than repeatedly switching accounts within the same environment.

It is important to emphasize that the goal of a Fingerprint Browser is not to create abnormal differences but to provide each account with a consistently stable usage environment over the long term.

What scenarios are Fingerprint Browsers typically used in?

In practical applications, Fingerprint Browsers are most commonly found in the following scenarios:

- Daily operations of multiple stores in cross-border e-commerce

- Management of social media account matrices

- Grouping and permission isolation for advertising accounts

- Unified management of account usage environments in team collaboration

The commonality of these scenarios is:

There are many accounts, the usage period is long, and it is necessary to avoid environmental cross-contamination between accounts.

Therefore, Fingerprint Browsers are more of a scalable operational tool rather than a means specifically for high-risk operations.

Advantages and Limitations of Fingerprint Browsers

Functionally, the advantages of Fingerprint Browsers are very clear:

- They can effectively isolate the browsing environment of multiple accounts

- Reduce the risk of account association due to repeated device characteristics

- Suitable for long-term, multi-account, stable operational scenarios

However, at the same time, they also have inherent limitations.

A Fingerprint Browser itself does not change the network exit.

If there are anomalies at the network layer, such as frequent IP changes or unstable network paths, platforms may still trigger risk control based on these signals.

This is why, in practical use, Fingerprint Browsers often need to be used in conjunction with network tools and cannot solve all problems on their own.

What does a VPN do? What layer of problems does it solve?

Unlike Fingerprint Browsers, VPNs address network layer issues.

With a VPN, users can:

- Change the IP address used when accessing platforms

- Adjust the geographical exit location of traffic

- Obtain a more stable or secure network connection

However, it is important to clarify that VPNs do not change the browser fingerprint itself.

In other words, even when using a VPN, the browser will still expose the original device and environmental characteristics.

Therefore, the relationship between the two can be understood as follows:

A Fingerprint Browser focuses on whether you "look like an independent device";

A VPN focuses on "where your network exits".

Why can "just using a VPN" still lead to risk control?

A common misconception is that:

As long as you use a VPN, your account will definitely be safer.

However, in today's platform judgment system, this logic does not always hold. The issue is not that VPNs are ineffective, but that platforms no longer rely solely on a single network parameter to assess account risk.

From the platform's perspective, what it truly cares about is not whether you "used a VPN," but whether an account has been in a reasonable and stable usage environment for a long time. If the same account frequently appears at different network exits in a short period, with constantly changing IPs and geographical locations, but without matching natural usage behavior, this "jumping" network characteristic itself may be seen as an abnormal signal.

On the other hand, VPNs do not change the environmental characteristics at the browser and device level. Even if the network exit changes, the browser version, system information, and operating habits remain consistent. When a device and behavior that "looks like the same person" appear alongside a constantly changing network environment, this inconsistency is more likely to attract the system's attention.

Therefore, platforms are more inclined to identify whether an account is naturally active in a long-term consistent usage environment rather than whether a certain tool is being used. For most users, the issue often lies not in "whether a VPN is used," but in whether the usage method is stable and continuous enough, and whether it aligns with the long-term behavior characteristics of real users.

When a single VPN is not enough: The reality of multi-session isolation emerges

After understanding that platforms care more about "long-term consistency," many users will discover a new reality problem:

Not all scenarios involve just one account.

In practical use, some people do not require complex fingerprint customization and are not engaging in high-intensity multi-account operations, but they still encounter a dilemma—when using multiple accounts simultaneously, they have to share the same network environment.

For example, logging into multiple accounts for daily operations at the same time often requires constantly disconnecting the VPN, switching nodes, or repeatedly logging in and out of accounts. This operation not only interrupts the usage process but also easily exposes different accounts to the same network exit, bringing unnecessary association risks.

In other words, the problem is not about "whether to use a more complex tool," but rather whether there is a way to keep different accounts relatively independent at the network level without increasing management costs.

It is under such demand that a lighter solution has gradually emerged between traditional VPNs and Fingerprint Browsers: VPN Containers.

VPN Containers: A solution between VPNs and Fingerprint Browsers

In some practical scenarios, users do not need complex customization of device fingerprints but want to avoid multiple accounts sharing the same network environment. For such needs, the traditional VPN's whole-device connection method is often not flexible enough, while Fingerprint Browsers seem too "heavy".

For example, the VPN Container feature launched by Surflare does not achieve isolation by simulating different devices but instead breaks down the use of VPNs from "the whole device" to "individual browsing sessions". On the same device, different sessions can establish their own VPN connections, thus maintaining relative independence at the network level.

In practical use, this method typically manifests as:

- Creating multiple isolated browsing sessions on the same device

- Each session can use independent VPN connections and IPs

- Cookies, session states, and browsing histories are not shared

This design does not pursue high customization of device fingerprints but reduces direct conflicts between multiple accounts during use through isolation at the session and network layers. For scenarios that do not require complex fingerprint management but wish for parallel multi-account use with a clear environment, VPN Containers are often a more user-friendly and lower management cost option.

Fingerprint Browser, Traditional VPN, VPN Containers – How to choose? Starting from needs

The comparison among the three is as follows:

1) What problems does each solve

| Tool/Function | One-sentence understanding |

|---|---|

| Fingerprint Browser | Isolates browser/device environments, making different accounts appear to run on different devices. |

| Traditional VPN | Changes the network exit and IP of the entire device for stability, regional exit, and other needs. |

| VPN Containers | Refines VPN usage to the session level, allowing different sessions on the same device to use different VPN connections and IPs. |

2) Core capability comparison: Looking at "what changes"

| Comparison Point | Fingerprint Browser | Traditional VPN | VPN Containers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changes browser fingerprint | Yes | No | No |

| Changes IP / exit | Needs to be used with a proxy or VPN | Yes (whole device) | Yes (per session) |

| Network exit granularity | Depends on configuration | Shared by the whole device | Independent for each session |

| Multiple accounts online simultaneously | Supported | Supported but with limitations | Supported |

| Are accounts easily sharing the network environment? | Avoidable (needs configuration) | Yes | No |

3) How to choose: Quickly match based on usage scenario needs

| Your Need | More Suitable Choice |

|---|---|

| Single account long-term use, focusing on network connectivity/exit region | Traditional VPN |

| Multiple accounts long-term operation, needing independent browser environments | Fingerprint Browser (usually needs to be used with network tools) |

| Multiple accounts online simultaneously but do not want to frequently switch VPNs; mainly want session and network isolation | VPN Containers |

| Strong risk control, large account scale, needing finer environment management | Fingerprint Browser + VPN (or VPN Containers) |

Summary:

Fingerprint Browsers solve the question of "Do you look like different devices," Traditional VPNs solve "Where do you access from," and VPN Containers solve "Do multiple sessions have to share the same network environment."

Therefore, these three are not mutually exclusive but complementary tools that solve different problems at different levels.

Summary: What really matters is "long-term consistency"

Whether it is a Fingerprint Browser, VPN, or VPN Container, they essentially address the same issue:

How to present a reasonable, stable, and consistently long-term usage environment to the platform.

The tools themselves are not the key; what truly determines the outcome is whether you understand the platform's judgment logic and choose a solution that matches your usage scenario.

FAQ

1) Does a Fingerprint Browser "change the IP"?

No. A Fingerprint Browser mainly addresses the isolation of the browser environment and local data, allowing different accounts to operate in different independent environments. The IP belongs to the network layer and typically requires VPNs, proxies, and other network tools to change.

2) Why can clearing cookies or using incognito mode still lead to recognition?

Because cookies are only part of the account status. Many platforms also integrate device and browser environment characteristics (such as browser version, time zone, fonts, WebGL/Canvas, etc.) for judgment. Even if cookies are cleared, these environmental characteristics may still remain consistent.

3) What is the difference between a Fingerprint Browser and "multiple browser windows"?

Regular multiple windows often still share the same browser environment and some local data; a Fingerprint Browser emphasizes "independent profiles," allowing cookies, local storage, fingerprint parameters, etc., to be isolated between different accounts, thereby reducing environmental cross-contamination.

4) If I only use one account, is it still necessary to use a Fingerprint Browser?

Usually not necessary. Fingerprint Browsers are more suitable for multi-account, long-term operations that require environmental isolation. If your main need is network stability or connection security, a VPN is often a better match.

5) Why can "frequently changing IPs" sometimes trigger verification more easily?

Because platforms often place more importance on long-term consistency. Frequently changing network exits and behavioral environments may be deemed abnormal signals by the system. Whether you need to change the IP depends on your actual scenario and usage method.

6) In what situations are VPN Containers suitable?

When you need to log into multiple accounts simultaneously but do not want to repeatedly disconnect or switch VPN connections, and wish for different sessions to be isolated at the network level, VPN Containers offer a lighter approach. They focus on session and network exit isolation rather than deep fingerprint customization.

7) Can Fingerprint Browsers be used together with VPNs or VPN Containers?

Yes. Fingerprint Browsers address isolation at the "device/browser environment layer," VPNs address the exit and connection at the "network layer"; VPN Containers further refine network control to the session layer. In multi-account, long-term operations, combined use is common for more complex needs.

Further Reading:

What are VPN Containers? Do they solve problems that traditional VPNs cannot?

John Wyatt

John Wyatt